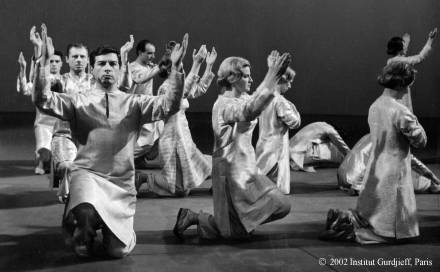

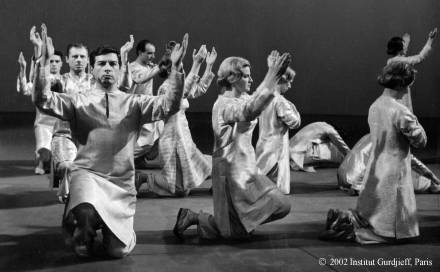

Does this sound familiar? Earlier today I had an argument with a friend, this afternoon my boss told me there will be no raise this year, and just now, the Movements instructor didn’t acknowledge me when I walked into the room. To make matters worse, he now announces he wants to start with a movement for which there is no music—I have to improvise. How can I find corresponding music in my state? Suddenly, I go from feeling down to feeling fear.

Where do I go to find what I need? To my head, of course. It’s like going to the attic of my house and rummaging around in the trunks up there to find something that will do.

But the head’s contribution is simply not enough. I need the attention of the other parts to play for movements. The body actually, physically, plays the piano, but is tense in response to the emotions which are cranked up in fear. The feeling is the only part of me that is subtle enough to perceive the Movement but it is not available to me right now.

These are hardly the ideal conditions for expressing the Sacred.

I begin to play—from my head—and the music is stale, dead and routine. The instructor looks over at me, which only serves to make me clutch up all the more.

What to do?

Why am I afraid? Because I feel inadequate to the situation. But the fact is I am inadequate. Gurdjieff’s Movements exist on a level far above me, and so does appropriate music. Any attempt to correspond from my level by “doing” anything is doomed to failure. And, yet here I go again, resorting to my bag of tricks.

I’m inadequate to the demand, not only because I’m in a negative state, but also because I’m stuck in my vain attempts to “find” something from what I “know.”

I have often heard of the Unknown; I’ve read books about it, and even purport to be in favor of it. So now, here it is, right in front of me. I don’t know what music would be appropriate. I don’t know how to produce something appropriate. I don’t even know how to bring the whole of myself to the situation: I’m truly in front of the Unknown. And I’m trying everything I can think of to get away from it.

The poet Robert Frost wrote, “two roads diverged in a wood. I took the one less traveled by.” I am at a fork in the road as I sit there playing my dead music. One road—the one I usually take—goes toward the Known, the other—“less traveled by”—goes toward the Unknown. What would induce me to take this “other road?”

First of all, I have to be convinced that the road I’m on is unsatisfactory, and this may take many years. But I won’t make the choice of seeking the “other road” unless I’m truly desperate.

Second, I have to have the courage to fail. There is no way to go into the Unknown while keeping one foot in the Known; it’s all or nothing. The Sufi image is throwing oneself into the flames.

Third, I have to be able to relax. All my dubious “self-control” is bound up in an ancient network of tensions that seems to come into play by itself. So I have to relax in the midst of action, while I’m afraid, while the Movement is going on, while I’m playing my habitual drivel in A minor.

Fourth, I have to be able to attend. The head must be clear, and glued to the class. I must be there with the class, with each footfall, with each position.

But I came into the class in a negative state. How do I get to a place where I can even make these efforts?

In an essay on attention, Thomas de Hartmann describes how a certain dog never took his attention off his two young masters. Never. As he said, “This is already a high degree of attention … much stronger than many humans have.”1

I too have noticed the attention of dogs. Up and down the avenues of New York, in front of every grocery store or coffee shop, dogs of all sizes and descriptions are tied up waiting for their masters to come out. Nothing distracts them. Their eyes are glued on that door. Why? Is it will? Is it wish? They’re dogs, after all. Do dogs have will or wish? In my opinion, it’s love. Their beloved is behind that door, and love directs their attention. Love keeps it there.

And it is the same with us; what we love draws our attention.

As I sit there, locked in fear and playing pap, what do I love? What am I concerned about? If I am very honest, I see that in one way or another, I’m concerned with myself: my self-image, my self-love, my vanity. What concerns me most is, “How am I doing? What do people think? How can I shine?”

To love the Movement is a very high aim. For now, at least I strive to care about it. I’m here for that: to bring music that helps the Movement come to life, that helps the class know how to move. They should feel that my music supports them, as if the music were under them, carrying them. And so, if I bring my attention entirely on the Movement in this way, suddenly I hear the sounds that I’m producing. I hear their inappropriateness and begin to care about that, too. I see that the sounds are my means for caring for the Movement and the class.

Suddenly, without my “doing” anything but paying attention, my feeling is called to join in the effort, and the body follows.

So, if “all” my attention is on the Movement and the sound, rather than my self, who is it that comes up with the music?

I have to trust something else in myself. But trust what? And how do I find it? Trust means not asking “what.” Does the baby look with suspicion at the mother’s breast? Does the flower look askance at the sun? And asking “how to find it” is another trick of the head, trying, as always, to maintain control. The head can’t know anything about this. What is needed is in the Unknown. I don’t find it, it finds me, and it comes by itself. Not because I “find” it or “want” it or even deserve it, but because I need it. I have thrown myself on the flames.

But putting all my attention (or care) on the Movement and the sound and letting “something else” create the music—even for a second—shows me immediately what I am up against. “Not knowing” is extremely unsettling. The urge for the head to take over is almost irresistible.

Giving up the need to know—taking this “other road”—is the price to pay if I wish to produce alive, fresh, creative, new, touching (and most importantly, corresponding) music.

Mr. Gurdjieff says that we have to pay in advance. The musician has to give up the luxury of knowing in advance. This is his payment.

This is also true for playing the written music. It must be played as if I don’t know what’s coming, again trusting “something else” to inform my playing.

So, I am in front of a great paradox. The music is coming from me, but I’m not “doing” it. I have to be relaxed, and at the same time, I have to be very much there, attending to what needs my attention: the class, the sound, the Movement.

As Madame de Salzmann once said: “You can’t do it, but it won’t be done without you.”

| Copyright © 2002 Stafford Ordahl This webpage © 2002 Gurdjieff Electronic Publishing Featured: Spring 2002 Issue, Vol. V (1) Revision: June 1, 2019 |

Stafford Ordahl joined the Gurdjieff Foundation in New York in 1960, where he was a member of Dr. and Mrs. William Welch’s group. Soon thereafter, he began his studies of playing the Gurdjieff/de Hartmann music and playing for the Movements with Mrs. Annette Herter (a pupil of Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann). In the early 1970s, he studied with Yvette Grimaud, who accompanied the Movements in Paris. In recent years, Ordahl has participated in public concerts of the Gurdjieff/de Hartmann music in Miami, Toronto, Phoenix, and New York. He travels frequently to various cities in the United States and abroad to share his understanding of the work on music.